It is said the last three piano sonatas of Schubert are suffused with premonitions of his death. It may be so, but the contemplation is often sweet, as if Schubert cannot help being so in his music and, thus, so as well in his preparations for death.

They are piano sonata 19 in C minor, D. 958; 20 in A major, D. 959; and, 21 in Bb major, D. 960. They are long, D. 958 over half an hour, the other two three-quarters of an hour. The length is temporal, not aural. A similar phenomenon occurs in the compositions of others; repeatedly, for example, in the performance of Wagner’s Ring, where even the longest acts seem to go by more quickly and acutely despite their actual temporal length.

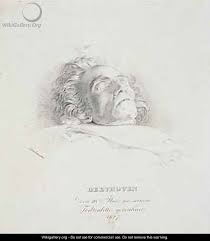

Schubert was 31 when he died, twenty months after the death of Beethoven. Like Beethoven’s final three piano sonatas, Schubert’s three sonatas written between the spring and autumn of his year of death are also considered a trilogy. All are similarly structured, being in four movements: a first movement in moderate tempo in sonata form; a slow movement in ternary A-B-A (D. 958 in A-B-A-B-A) form; a dance movement in ternary form, with trio; and, a finale in sonata-rondo form. Much has been written regarding Schubert’s use of Beethoven’s musical and structural devices, including the illusion of stasis that creates a sense of time that is motionless.

There are relationships within the music itself that seem to me inescapable to note. Much, for example, has been made the sudden trill in the eighth bar of the first movement of the Bb major sonata; yet even so masterful a pianist as András Schiff remains, after decades of deeply knowledgeable study and performance, uncertain what it may represent. Many have also commented that the finale of the sonata falls short of the quality of the first two movements. I do not think this is so, but it takes long reflection to be able to make some sensible response to the whole of the sonata. If, indeed, as some say, the trill is a premonition of death, and the finale too bright in manner, then I offer that the finale, especially in the context of the interjections that are throughout the preceding scherzo, may be a statement that insists on the gladness of knowing that one remains alive, however close to death. And though the finale’s opening theme and its mutations press upon the inner ear of the mind, it is the trill that, ultimately, remains omnipresent, and persistent in whatever, without words, it evokes.

The complexity and innovation evident in these sonatas certainly dispose an interested listener and student to an awareness of the difficulty of understanding artistic creations, no matter how often one comes to them, for there is so much in them that it requires humility of intellect and feeling to make manifest what and how they communicate. But, this is one of the beautiful mysteries of artistic creation.

***

8 February 2016

The András Schiff recital, yesterday afternoon at the Vancouver Playhouse, was exceptional. The sadness that languishes in Beethoven’s Op. 110 and the sadness that is resigned and angry in Schubert’s D. 959 were evinced with great artistry. The house was sold out and the audience enthralled. What a great privilege it is to be in the presence of such artistry, and to learn. The second recital is tomorrow evening.

10 February 2016

The day strikes me differently after hearing András Schiff, in concert yesterday evening, playing Beethoven’s Op. 111 in a way, a revelation, that I had never heard, and Schubert’s D. 960, with such conviction of coherence and awareness that it turns sadness of mind into its brilliance.